Photo by RUN 4 FFWPU from Pexels Photo by RUN 4 FFWPU from Pexels Last Thursday, I hosted a Run For Your Life session which combined walking, jogging and running - a type of session called fartlek (Swedish for "speedplay"). I was asked by one of the participants whether this is what they should be doing during a race. Great question! Let's say you're at Parkrun and you know can't run continuously for 5 km, then it's absolutely fine to intersperse your running with the occasional walk to catch your breath. This is a great way to make longer distances achievable, particularly if you are new to running, or to that distance. However, if you know you can run the distance and want to maximise the speed overall, then you will find it best to run either at a steady pace, or run slightly faster in the second half of the race than the first. In practice, most people tend to run a bit too fast at the start, and steadily slow down during a race. This means early exhaustion, and spending most of the race tired! If you can learn to pace yourself early on in the run (which is much harder than it sounds), you will have the energy left to speed up in the second half. So why do we often vary speed in training? Going for long, steady runs according to the distance you are training for is great, and is something that any long distance runner would want to have as the mainstay of their training programme, but there are several benefits to adding speed intervals:

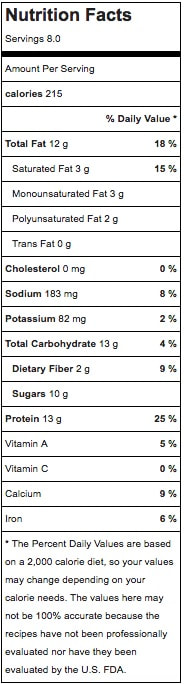

Runners World: www.runnersworld.com/uk/training/motivation/a775858/4-interval-running-sessions-for-any-race-goal/ Runners Blueprint: http://www.runnersblueprint.com/interval-running-workouts-for-speed/  I us I developed these bars as a low-cost, low-sugar alternative to shop-bought protein bars (which also come in environmentally disastrous non-recyclable wrappers). The recipe is easy and quite adaptable. The protein comes from a mixture of milk, nuts and seeds, as well as protein powder. Most of the sugar comes from the sultanas, which can be reduced if you want to really cut down, but I find that they add a lot to the texture and flavour. 30 g (1/2 cup) Hot Oat Cereal (finely ground instant oats without added sugar or flavours) 60 g (1/2 cup) Dried Skimmed Milk 2 Scoops (50 g), Whey Protein - Chocolate flavour 25 g Pumpkin Seeds 50 g Ground Almonds 20 g Desiccated Coconut 70 g Smooth Peanut Butter With No Added Sugar 60 g Sultanas Mix all ingredients together and add enough water to make a firm dough (about 3-4 tbsp). Roll or press the dough to about the thickness of a brownie. Refrigerate until solid, then cut into eight portions with a sharp knife. The portions can be eaten straight away, kept refrigerated for 3 days, or frozen and removed individually as needed. I usually make a double quantity, and freeze the bars down. Please note that the nutrition panel to the right is based on an automated generator by entering the recipe into My Fitness Pal. It is therefore only as accurate as the crowd-sourced data used in its production!  Most people will suffer from back pain at some time in their life. In fact, it's one of the biggest causes of time off work, causing 12 million days of absence every year in the UK. Knowing how best to treat it is therefore of great importance for enhancing wellbeing among the general population and in the workplace. The trouble with back pain, from a scientific point of view, is that it usually get better by itself within a few weeks or months. So you can't necessarily rely on the word of your friends as to what helped them to recover from their episode of back pain - perhaps they would have felt better then anyway? Even scientific studies of back pain treatments may lead to mixed conclusions, due to differences in protocols or statistical flukes. Systematic reviews, which methodically combine the results of the best quality research trials provide the high standards needed for evidence-based medicine. Three scientists from the University of Poznań, Poland, compiled a helpful review of the latest research into the effectiveness of Pilates in treating chronic non-specific low back pain. They found three systematic reviews since 2014 which looked at the results of dozens of randomised controlled trials comparing Pilates to controls (no exercise) and other interventions, such as cycling, general exercise, the McKenzie method, trunk strengthening exercises, and massage. Pilates was found to be effective at treating back pain, when compared to the controls, with a similar level of effectiveness to the other exercises.

Of course, the benefits of Pilates aren’t limited to treating lower back pain, and three recent studies comparing the effectiveness of Pilates with other methods widely used in managing lower back pain - the McKenzie method, trunk-strengthening and extension-based exercises - found that the Pilates group improved other aspects of health alongside the pain being treated. Think of it as the side effect that everybody wants! Thinking of joining STRONG by Zumba®, the unique high intensity interval training class where the music is synced to the workout? Here are my top six tips to get you started!  1. You need the right kit. I’m not talking about branded clothing. I mean a decent pair of trainers, stretchy clothing in which you won’t overheat, and for the ladies, a high support sports bra. You want a pair of cross trainers that grip well on a hard floor, with cushioning and some flexibility in the sole. Depending on the sensitivity of your skin, you may also wear fingerless gloves, to protect your hands as you press up and burpee. Also, make sure you arrive well-hydrated, and bring a bottle of water to keep you going during the class. Looks are secondary. Nobody else is going to mind what you are wearing. 2. It’s not a competition. Well, not against anyone else in the room. STRONG by Zumba® is an intense workout, but modifications are included at every step to either make the class more accessible to beginners, or challenge the fittest of participants. Before starting a new exercise programme, it’s wise to check with your doctor whether it’s suitable for you, particularly if you have any ongoing health conditions.  3. Pay attention to the technique cues. These help you to exercise safely and effectively. If something doesn’t feel right - ask! We move quickly from one move to the next, so there is little time for refining technique in the middle of the class. However, don’t be shy of asking about a particular move before or after class - your instructor is passionate about good form and will love the opportunity to coach you to move better. 4. It’s not a dance workout. Zumba may be famous as a dance party workout to amazing global music, but this is different. There is no hip-wiggling or arm lines; the exercises would be familiar in a circuit training class (think squats, burpees, kicks) but the music is still as awesome as you’d expect from Zumba, and will motivate you to work harder and help you fall in love with the class.  5. It might hurt. But not in a bad way. You may feel your muscles burning during class, or becoming stiff over the next couple of days. This is a normal response to hard exercise - and it’s up to you whether you push it to that level (see tip #2). However, any pain that lasts more than a few days, or is in the joints, rather than in the muscles, is not part of the plan. In this case, don’t suffer in silence; it can often be resolved by improving your technique, or occasionally it may need checking out by your physio. 6. You will burn lots of calories! This the magic of the music. In controlled experiments measuring the calories burned by participants doing the same workout either with or without the STRONG by Zumba® music, those working to the music burned an average of 48 calories more per session. On top of that, due to a phenomenon called EPOC (excess post-exercise oxygen consumption), which occurs after high intensity interval training, you will continue burning more calories than at rest - about twice as many, in fact - for about 40 minutes after the class finishes. I teach STRONG by Zumba® on Monday and Tuesday evenings - contact me to book!

Gymnastics. Sport of the young. The youngest athletes in the Olympic games, with an average age of female athletes being just 19. But it isn’t a hard and fast rule that gymnasts retire young. Turning that rule - and herself - upside down is Johanna Quaas, still competing in her nineties! Born in Saxony, Germany, in 1925, Johanna is a few months older than the Queen. She took part in her first gymnastics competition in 1934, and although her career was interrupted by World War II and a subsequent ban on gymnastics by the Allied Control Council until 1947, she never lost her love of the sport. Following her marriage and the birth of three children, Johanna became a PE teacher and coach to young gymnasts, but did not resume competing. According to website sixty+me.com, “people take one of two paths in their sixties. Either they become a more extreme version of the person that they have always been. Or, they broaden their perspective and become the person that they always wanted to be. Johanna is a shining example of someone who focused on her potential, not her past.” And so it was that in 1982, inspired by meeting up with some former gymnast friends, she started training and competing again, going on to win 11 medals from the German Championships. In 2012, she was certified as the World’s Oldest Gymnast by the Guinness World Records. Here she is in a heartwarming interview, discussing her career: In 2016, she decided to “finish what the monarch had started” - referring to the Queen’s apparent parachute jump at the London Olympic Games opening ceremony. She claimed that parachuting is much easier than gymnastics, but I’ll take her word for it.

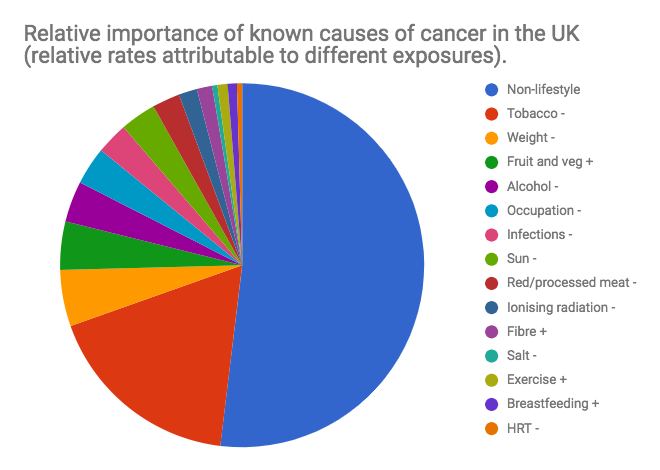

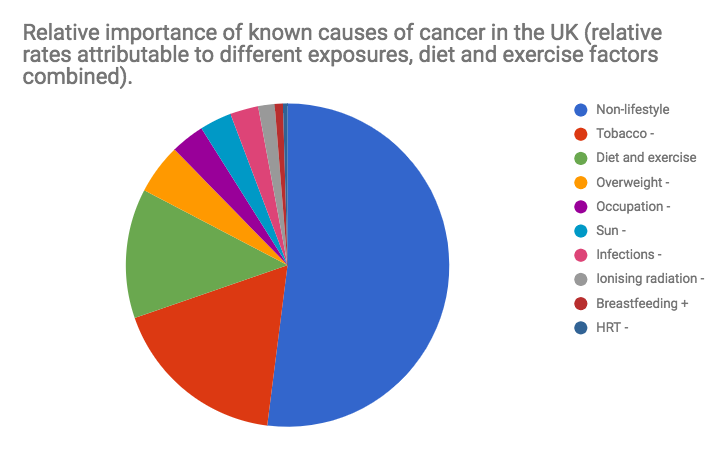

The only age-related problem that Johanna appears to suffer from is a scarcity of competitors in her own age category - she often has to compete against gymnasts up to 25 years her junior! In a 2017 interview with the Straits Times of Singapore, she said, “If you are fit, it is easier to master life … When there is movement, there is life." Mastering a new skill can be be an emotional journey. Understanding the route can help us to enjoy the ride. A practical guide on how we use failure to acquire mastery.  Last week, I joined a running club. I don’t mind confessing that I was quite nervous. I’ve been running a couple of times a week now for a few years, but the prospect of running alongside people who know what they are doing felt very intimidating. This is a club that I've heard has a few world record holders in its membership. And then there’s me, who jogs around the block and does the odd 5 or 10 k, but has never considered herself to be “a runner”. What if I couldn’t keep up? If I found myself halfway across the city, slowing everyone else down, having had the audacity to think I was worthy of being among them? If my running style is just really embarrassing? My rational side knew that I would be fine, but reason only has limited power to calm nerves. I reflected that learning is an emotional process, and that this is as integral to one's own self development as the skills and abilities themselves. When it comes to any new skill, there are stages we go through to achieve mastery. Educational psychologists often refer to the four stages of learning (1). In my experience as both teacher and learner, each has its own associated emotions.  Stage One - Unconscious incompetence: When you begin learning a new skill, you know that you have a lot to learn, but you may not be aware of where you are going wrong. In fitness, this might mean that you are moving in an uncoordinated way, or even unsafely. For example, in a squat you might roll your knees in towards each other, stick your behind out too much or let your chest drop, and when your teacher points it out to you, you may not realise that you were moving that way, nor even that they are mistakes. Stage Two - Conscious incompetence: Now you are aware of what you should be doing, but it feels unnatural and difficult, and can feel overwhelming. As soon as your knees are in the right place, your tail end sticks out. Correct that and you’ve forgotten that your chest is now bending forward. By the time you’ve fixed your chest, your knees have started rolling in again. It can be discouraging to always be aware of what you’re doing wrong, but it is a key part of the learning process. Stage Three - Conscious competence: With practice and correction, you will reach the stage where, when you’re focussed, you can practice with good quality. But, take your mind off what you’re doing and straight away you fall back into the old habits. A quick reminder, and you’re back on form. This is a motivating stage, where you start to feel a sense of progress. Stage Four - Unconscious competence: This is when your hard work has paid off. You’ve broken the original faulty habits, and now instinctively practice with good quality. Your sense of satisfaction is well deserved, but don't rest on your laurels! Now you are ready to challenge yourself with more advanced variations, knowing that you are moving from a secure foundation. You may find that you are back at stage one for the next level. In nearly every discipline, this cycle continues indefinitely. As we master one skill, the next skill is within our sights. Repeatedly making - and correcting - mistakes is an integral part of the learning process. This is why I like to encourage practice over perfection. If you are always practicing perfectly, you are no longer challenging yourself, and are at risk of boredom and a sense of lack of progress. As it turns out, my first trip out with the runners was absolutely brilliant. The coach was kind and skilled, and stayed back with me as I fell behind on the homeward stretch, and the others went off ahead. I continued: sweaty and bright crimson, but feeling welcome. Of course, the others weren’t in the least bit impatient with me - why would they be? - and I am quite sure that in time these strangers will become my friends.  My experience makes we want to offer an additional stage prior to the other stages of learning; as critical as any of the others, and one which I believe is responsible for the reluctance of people to take up new exercise regimes, or any other new hobby that they might aspire to. Stage zero - Overcoming fear: When you start something new, you know that you’re going to be bad at it. You know that the teacher is going to see that you are bad at it. Taking that first step of presenting your unskilled self to the teacher and other participants is something that the majority of people will be nervous about. But remember that no good coach or teacher will judge you for being a beginner. It is their job - and mine - to support you through the stages of competence, and guiding people towards improving their movement is what I am passionate about. Everyone has to start somewhere – so start in a place that is supportive. My top tips when starting a new class would be - arrive early so that you can introduce yourself to your teacher (tell them if you are feeling nervous!), know your limits, and remember that everyone else in the class was a beginner once, too. 1. Developed by Noel Burch, co-author with Thomas Gordon of the Teacher Effectiveness Training Book, 1974. Cancer Research UK (CRUK) recently launched a social media campaign aimed at raising awareness that obesity is the second biggest preventable cause of cancer, after smoking. I was alarmed. I then looked at the data supporting the claim and changed my mind. First up, it is important to realise that CRUK are only talking about preventable cancers. Fourteen factors have been identified, which are responsible for a total of 43 % of cancers in the UK. More globally, the World Health Organisation agrees that around 30-50% of cancer cases are preventable. This means that if you take a sample of 100 cases of cancer in the UK, on average, 43 of those cases could have been prevented were those people to have had optimal levels of the fourteen factors. 57 of those people, sadly, would have got cancer, no matter how healthy their lifestyle was, because their case was due to other factors, such as their genetics. Some slim people will be among these patients. This doesn’t mean that a slim person won't get cancer. It just explains how it is possible for overweight to be a cause of cancer, while slim people can still get cancer. CRUK’s claim failed to make clear that the majority of cancers are not known to be preventable, and in doing so, caused some confusion, so I have addressed this by drawing up a pie chart, using the same source data as CRUK, which as well as including the fourteen lifestyle factors, also includes the other "non-lifestyle" cancer cases, for which a preventable cause hasn't been identified. Smoking was found to be responsible for 19.4 % of all new annual cancer cases in the UK (in 2010). That’s the big red chunk responsible for more cancers than any other preventable factor. Excess weight was responsible for a further 5.5%, the fairly sizeable orange slice of pie. But, CRUK have taken a small liberty with the data - dietary factors (suboptimal levels of fruit and veg, fibre, red meat and salt) sum to 9.2 % of cancers. By dividing them up into small slices, they have downplayed the relative importance of a healthy diet. Add insufficient exercise to the list and you are up at 10.2 %, and alcohol brings it to 14.2%. This means that diet and exercise are nearly three times as important as weight! Let’s redraw that pie chart. Now diet and exercise become the second most important cause of preventable cancer (green slice), while overweight is demoted to a (still important) third place. CRUK are correct only insofar as the data support healthy weight being better than overweight. However, I hope that this persuades you that the person who eats healthily, avoids alcohol and keeps active, yet struggles to keep their weight down, is statistically far less likely to get cancer than the skinny couch potato who lives on bacon washed down with gin. The person who eats healthily, avoids alcohol and keeps active, yet struggles with their weight, is less likely to get cancer than the skinny couch potato living on bacon washed down with gin. CRUK have been accused of being judgemental about obesity. They are on a mission to educate people to empower them to make informed choices to reduce their own risk of cancer. 5.5 % may be a small fraction of the total, but that percentage relates to over 17,000 people per year in the UK. Over 17,000 individuals, each with families and friends. How could a responsible educator fail to make this point, for the sake of avoiding offence? I certainly hope that they had no ulterior motive to shame people who are overweight or obese. They do recognise that weight management is difficult in our environment, and are campaigning for changes which will help to make weight management easier, such restricting junk food advertising. However, given the relationship between diet, exercise and weight management, perhaps they could have promoted the more positive message, that an active lifestyle and healthy diet - lots of fibre, fruit and veg, avoiding salt, alcohol and red/processed meat - is the best thing you can do after not smoking to reduce your risk of cancer. Worrying about your weight should be a secondary concern when it comes to cancer. Cancer Research UK run the risk of encouraging unhealthy, fad diets By focussing on weight in their social media campaign, CRUK run the risk of encouraging unhealthy, faddy ways to lose weight, rather than sustainable, healthy choices. There is no conflict of the decision to make here, as staying active and keeping the identified dietary factors at optimal levels are consistent with advice to encourage weight management and more importantly, add up to a reduced overall risk of cancer.

When starting a new exercise programme, many people put their faith in exercise professionals to help them meet their goals and form new habits. Bad technique or inappropriate exercise choices can derail those plans, by being ineffective, dangerous, or both. Qualified instructors are trained to deliver safe, effective and appropriate exercises to their clients. However, in the UK, fitness instruction is not a regulated profession. Anyone can legally set up and teach a fitness class, or call themselves a personal trainer or Pilates teacher. Although they are unlikely to get insurance without appropriate qualifications, they won’t be prosecuted for earning a living by running classes or posting workouts online. The main problem with unqualified teachers is that they have not necessarily learned an appropriate level of anatomy and physiology for the exercises that they are teaching, so they may not be aware of what to look out for to ensure that you are exercising safely and effectively. But that's not all. They may give - with all the best intentions - false or misleading information based on their own experiences, which may not apply to everyone. They may not have been taught how to coach and motivate, risking leaving you confused and disheartened. They may not have had First Aid training. As fitness instructors progress through the levels of qualifications, they are increasingly able to accommodate people with injuries or medical conditions which need extra care. But note where the professional scope ends. As I am always at pains to point out, although your fitness routine may support your general wellbeing and recovery from injury, the fitness instructor’s job is to accommodate your injury (perhaps in conversation with your physiotherapist, or other medical professional) to allow you to exercise safely, and not to diagnose, treat or prescribe. Unqualified instructors are not bound by this professional code.  A simple way to tell whether your teacher is qualified is to check if your instructor is a registered exercise professional. REPs, the Register of Exercise Professionals, was developed to protect the public from trainers who do not hold appropriate qualifications and to recognise the qualifications and skills of exercise professionals. REPs members must keep their skills up to date with continuing professional development on approved courses. Not all qualified fitness professionals choose to be on the exercise register, so for non-members, here’s what you need to look out for: a group exercise teacher or gym instructor should hold a minimum qualification of a Level two certificate; personal trainers, yoga and Pilates teachers should be qualified to Level three. For exercise referral for specific medical conditions, you should look for a level 4 specialist qualification (Level 3 for pre- and post-natal). If you are unsure about whether the qualification that your instructor holds are valid and trusted, you can search the Register of Regulated Qualifications. Regrettably, some institutes offer certificates for superficial online courses without adequate assessment procedures. These will not be listed on the Register. Finally, remember that a person’s body is not their fitness qualification. There are plenty of excellent instructors out there who aren’t supermodels. Genetics, diet, age and medical history all play a part in the appearance of your body, and having a lean torso is no indication of whether a person is able to teach exercise. Many moons ago, as a young woman who was starting to take part in martial arts competitions, I took a fancy to the notion that I should probably “do Pilates or Yoga or something.” So it was that I went along to the village hall to take part in my first Pilates class. I was the youngest by a good three decades. Full of the arrogance of youth I was expecting to be some kind of gift to Pilates. Easy. But there I was, supposedly in peak condition, stuck doing exercises that I felt were doing nothing for me, while the harder exercises - which the older participants accomplished with ease - were completely inaccessible to me. There seemed to be nothing in between. I went to Yoga instead - in a more humble frame of mind - and didn’t return to Pilates for another seven years. Today, I would like to discuss how we can use progressions to form a bridge between the basic and the more advanced versions of any exercise. If we are to progress and improve our movement, we need to find our personal sweet spot for every exercise - where we are challenged, but can perform the exercise with good technique. We don't just have levels 1, 2 and 3, but instead a countless range of possibilities are open to us. These principles can be applied to any form of exercise. To vary the intensity of an exercise we can adjust:

Because we have so many tools in our exercise kit, it should be possible to find a version of each exercise that will challenge you and which you can perform safely. In the video below I demonstrate how just using two of these principles - lever length and base of support - can progress a simple exercise into a more advanced one through a series of small steps. You would typically progress through these stages over the course of a few weeks or months. It may be that, due to injuries or your body composition, for example, that some versions of a particular exercise will always be unsuitable for you; however, there is always something we can do to make an exercise effective and challenging. Finally, don't be shy to tell your instructor if an exercise isn't working for you - their job is to tailor exercises for you and ensure that you can execute them safely and effectively. I spent the weekend at a reunion with some old friends. On the Saturday morning, I rose early to go for a short run. One of my friends expressed concern that, although I may look fit and healthy now, I could pay the price in future with joint problems from running, and that she knew several people who were highly active in their youth, but in later middle-age suffered from arthritis and required joint replacement. People often come to the conclusion that running causes bad knees, after meeting older runners who suffer from knee pain, but another thing that happens during decades of running is ageing - and this will happen whether you run or not! Over a twenty year period, Professor James Fries of Stanford University studied a cohort of 538 runners (aged 50+ at the start of the study) and discovered that the runners developed fewer disabilities, enjoyed a longer span of active life and were half as likely as non-runners to have died during the study period. They had no more arthritis than non-runners. This may seem to defy common sense - surely joints wear out? - but cartilage needs motion and stress to stay healthy. Synovial fluid is stored in cartilage, and when the joint is used, the synovial fluid excretes from the cartilage and delivers nutrients and lubrication to the joint. Furthermore, impacts of 4.2 G or above have been found to strengthen hip bones - this can be achieved by running at a speed of a 10 minute mile (9.6 kph or 6:15 min/km), while slower speeds (more achievable for many people) can maintain existing bone strength.

The small nugget of truth, from which the larger myth has emerged, is that running when you are injured can lead to arthritis, and if you already have osteoarthritis and bone-to-bone contact, running could make it worse. Chris Troyanos, certified athletic trainer and the medical coordinator for the Boston Marathon offers some great advice: "Inherently, running is good and healthy for most people, but it's a matter of how you get started in it, and it's a matter of slow progression. However, there are body types out there that are not conducive to running. For example, people who are excessive pronators have the inside part of their feet drop inward more than it should when they're running. That causes stress on the feet and knees, so their bodies are naturally not great shock absorbers. People who have hyperextending knees ... are also going to have trouble running. Those who have some of these issues can run, but they may not be able to run more than a mile or two. When you're looking at starting a running program, one you might want to start with a walking program first, then make the leap to an easy running program. As you go through these steps of increasing your activities, it's important to listen to your body. If you are getting knee pain when you go from 5 to 7 miles a day, that could be your threshold for you. If you have any type of existing pain or discomfort in your legs, it's not smart to keep running." Making sure that you can maintain good running form by taking a holistic approach to your health - maintaining a healthy weight, a strong core, good alignment and flexibility will also help to ensure that you are doing more good than harm when you pound the pavements. And on that note, running on softer surfaces can also help to reduce impact - though watch your footing on natural surfaces! Listen to your body. If you run and it doesn't cause you joint pain, then you have no need for a nagging doubt that you will regret your choice decades down the line. If you used to run and now you have joint problems, there is no need to blame yourself. If anything, you may congratulate yourself for possibly having delayed their onset. |

AuthorFitness and Pilates instructor with a passion for science. Archives

November 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed